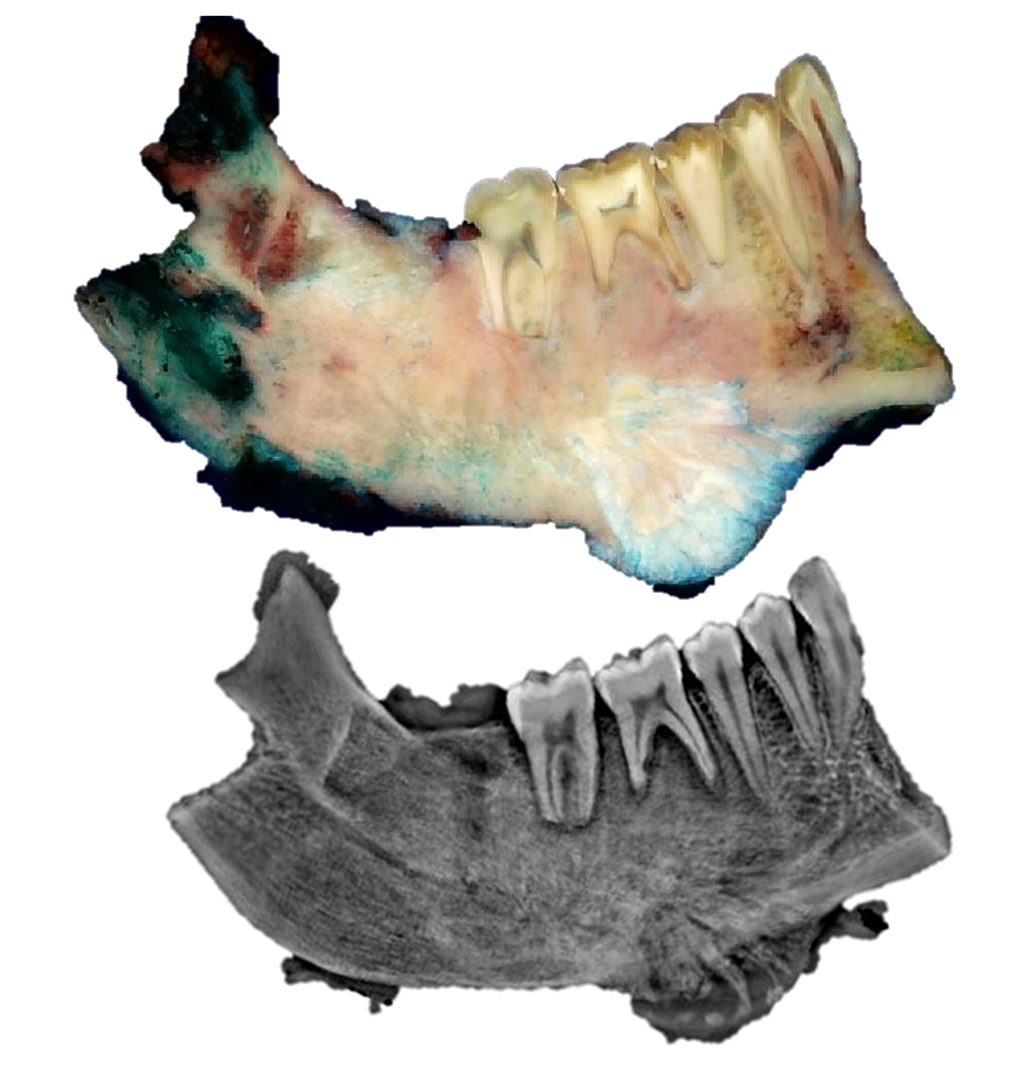

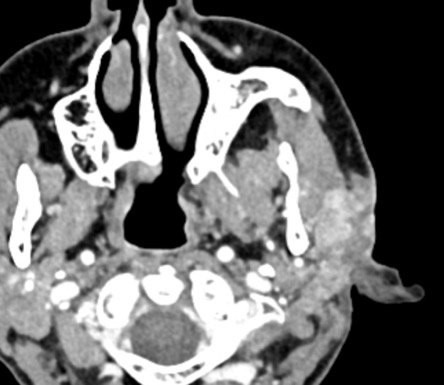

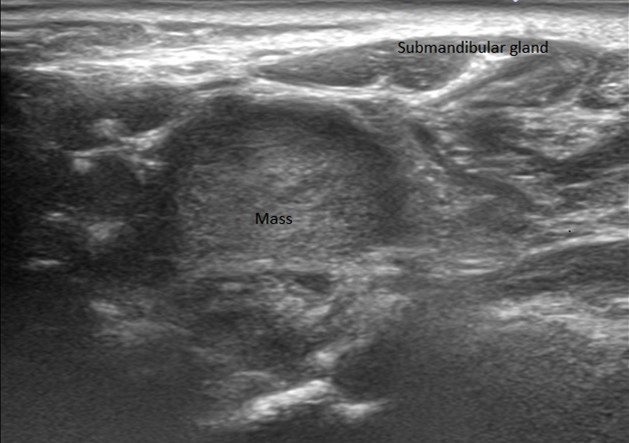

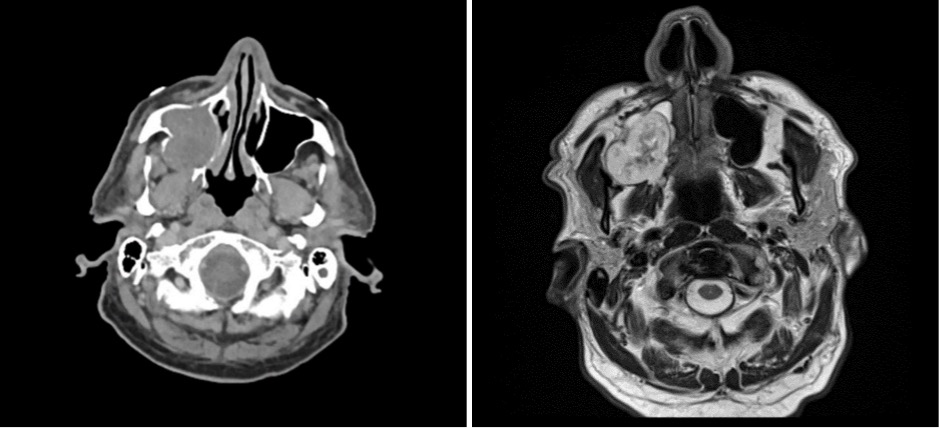

An elderly man presented with a maxillary sinus mass. Physical exam showed softness of the right hard palate and a nasal endoscopy showed a mass extending into the right maxillary sinus. A CT and MRI showed a mass within the right maxillary sinus with bowing of the medial maxillary wall and cortical breakthrough of the posterior wall. The mass demonstrated extension into the fat of the right masticator space and involvement of the right maxilla. A biopsy of the mass was performed. Representative imaging of the mass along with H&E stained sections and immunohistochemical stains of the biopsy are shown.

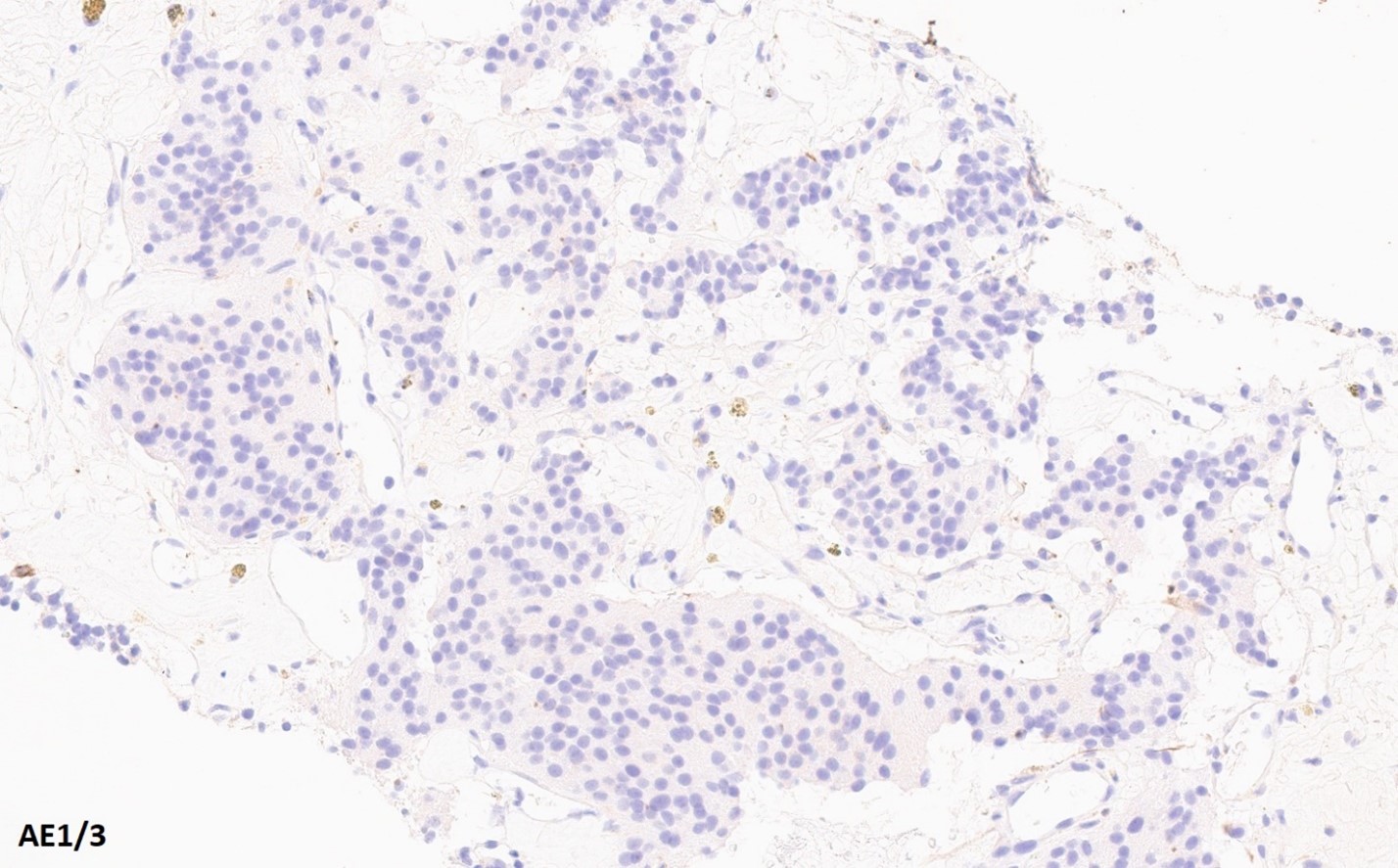

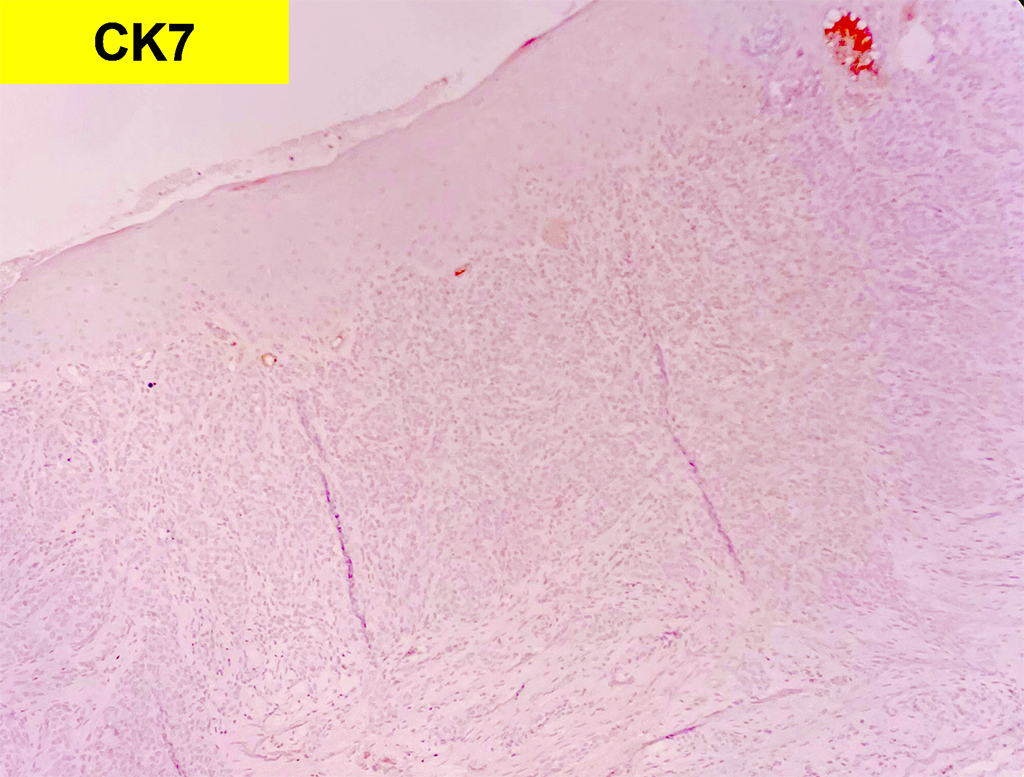

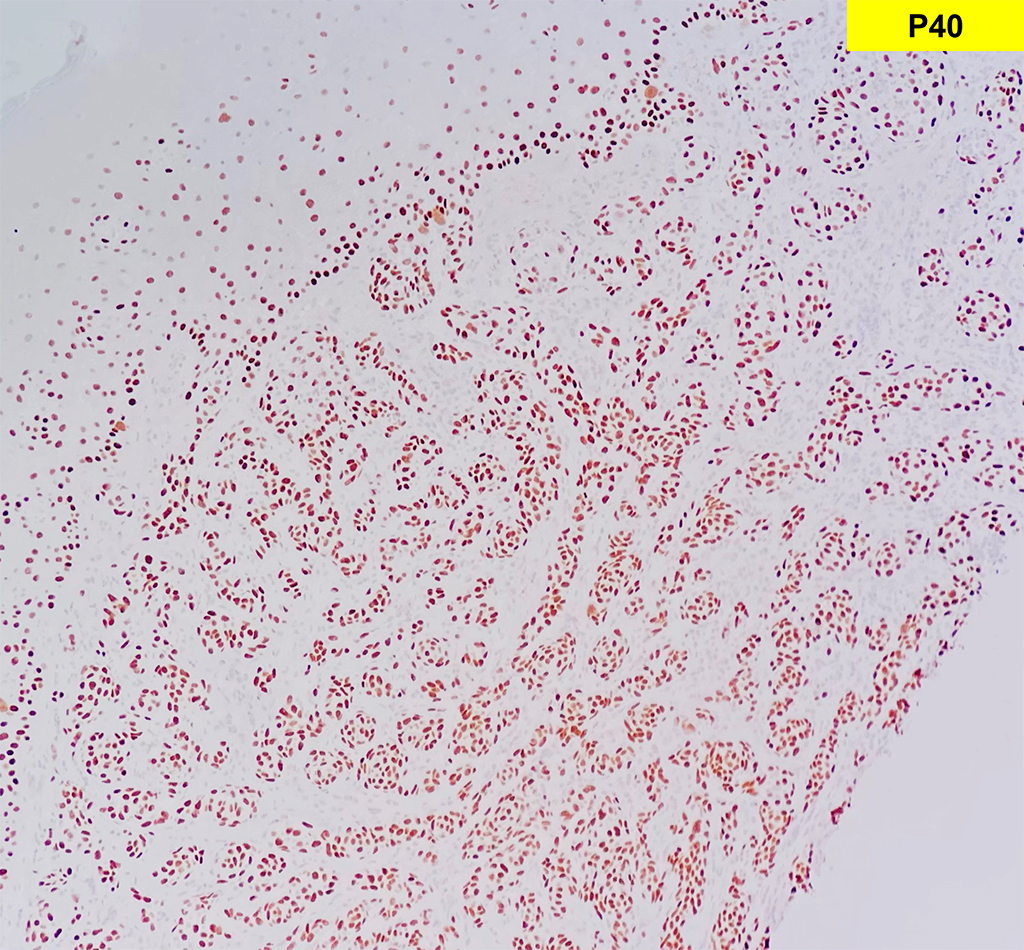

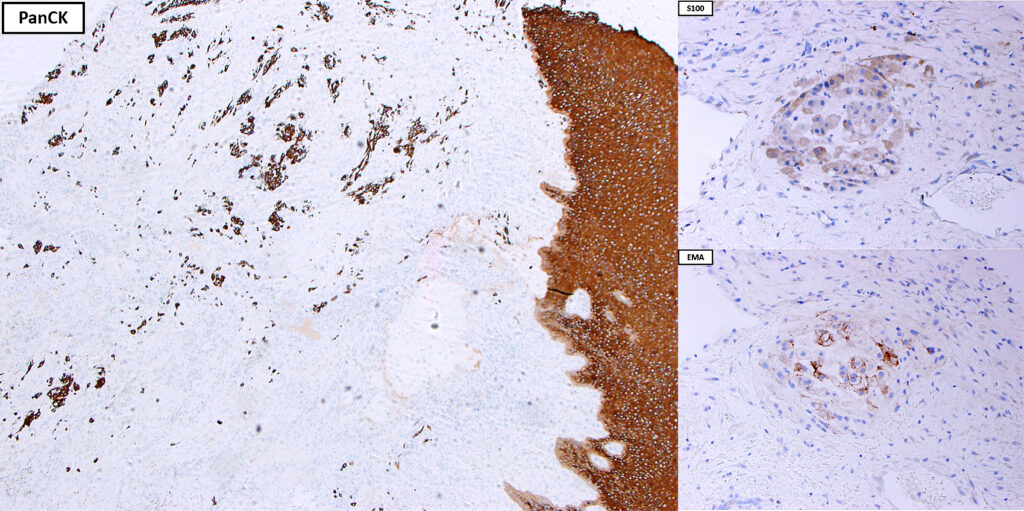

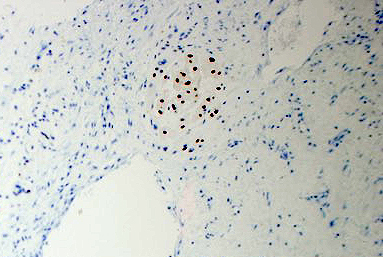

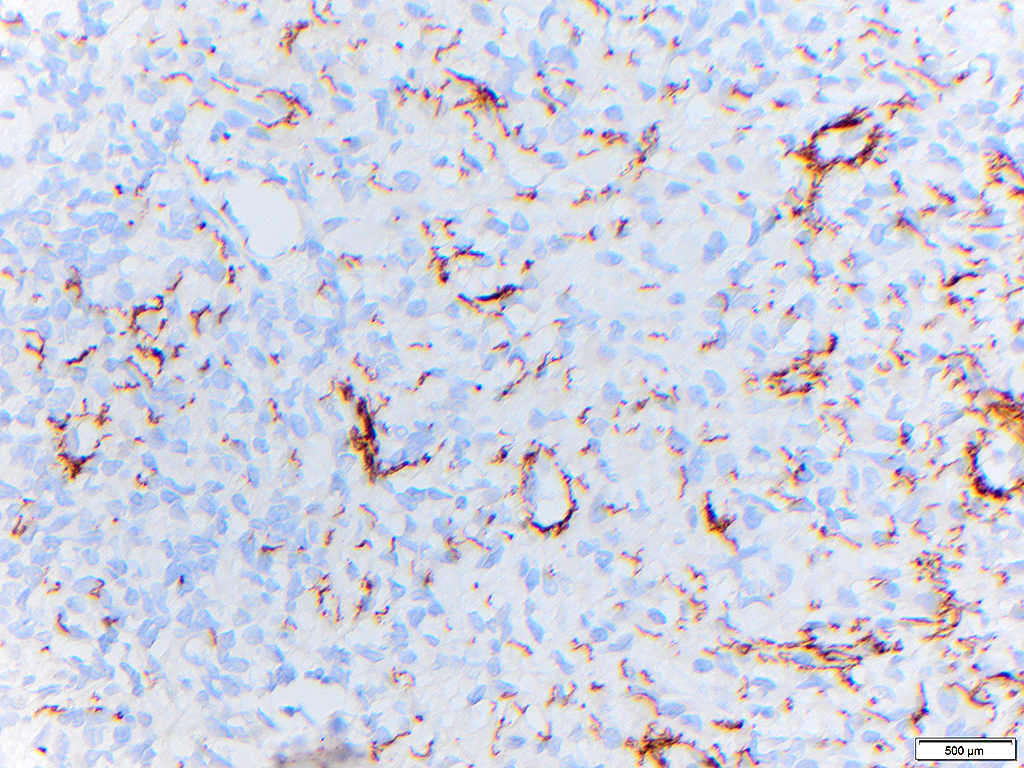

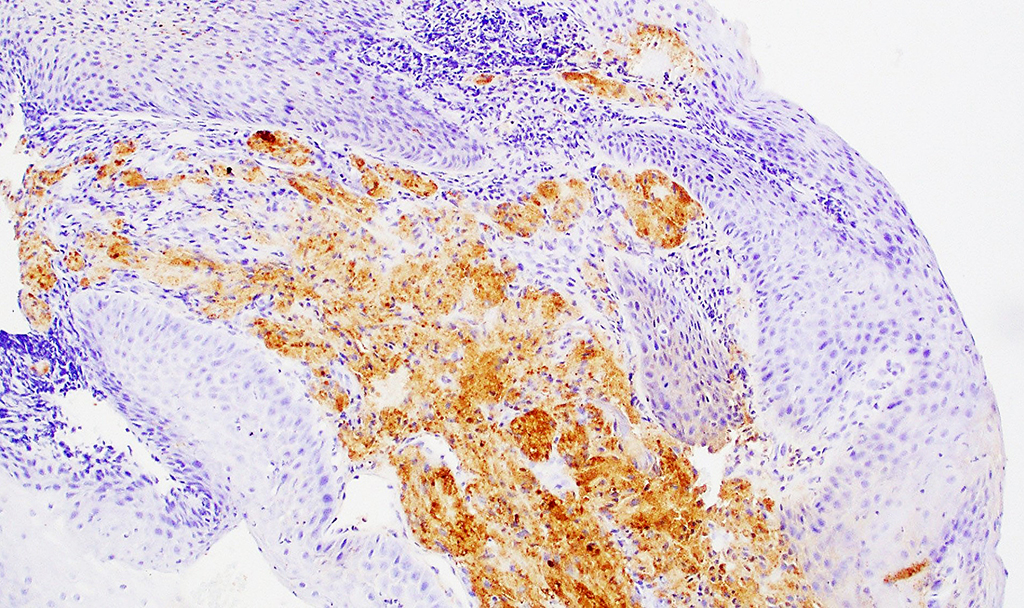

2. What is the immunohistochemical stain shown in the last image?

Metastatic Chordoma

Chordoma is a rare, low to intermediate-grade malignant neoplasm of bone that is derived from and phenotypically resemble embryonic notochord remnants. During embryonic development, the notochord serves as a primitive axial skeleton from the third/fourth week of gestation until the seventh week of gestation. Incomplete regression of notochord tissue along this notochord tract is thought to give rise to chordomas of the axial skeleton with the most common sites being sacrococcygeal region, craniocervical/base of skull, and vertebral column. Benign notochord cell tumors share a similar midline pattern of distribution and similar morphologic features with chordomas, suggesting that they may represent a precursor to chordomas, however, this remains controversial. Clinically, chordomas are typically identified within the 4th-8th decades of life.

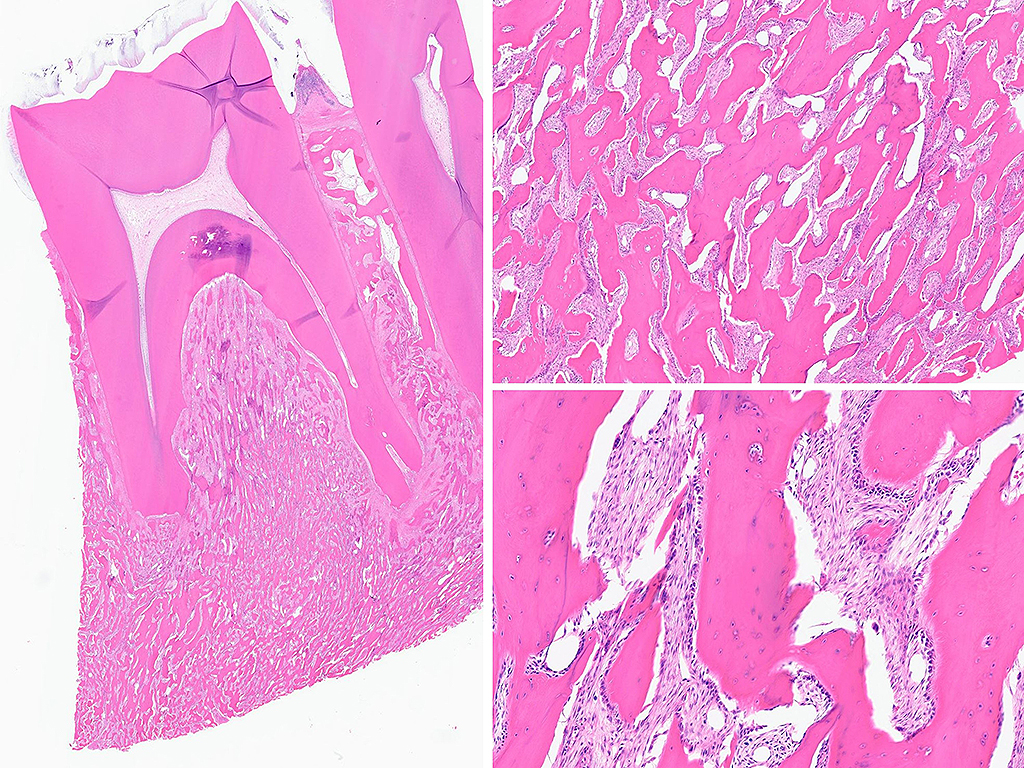

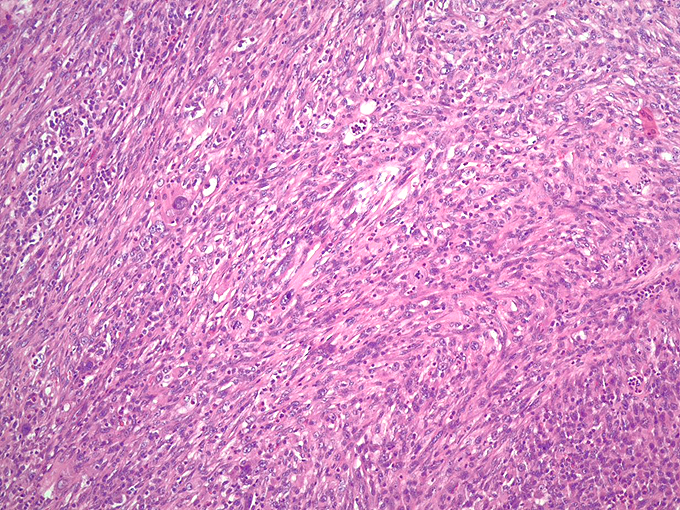

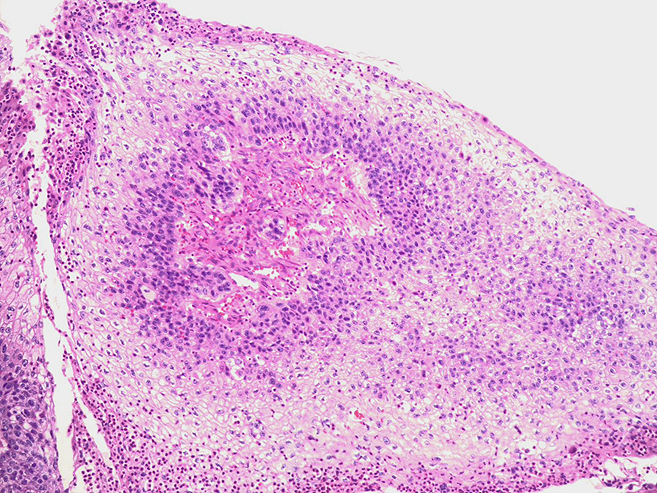

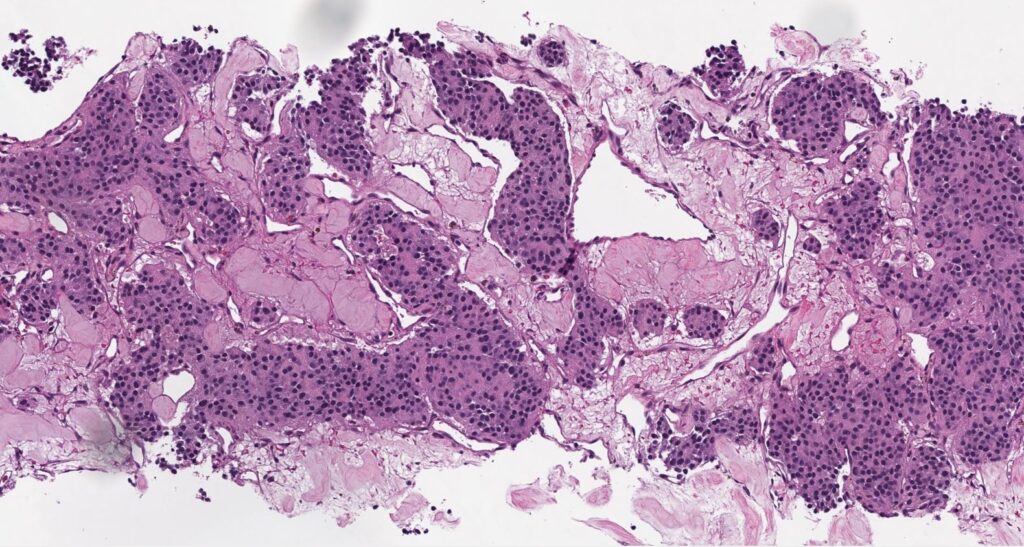

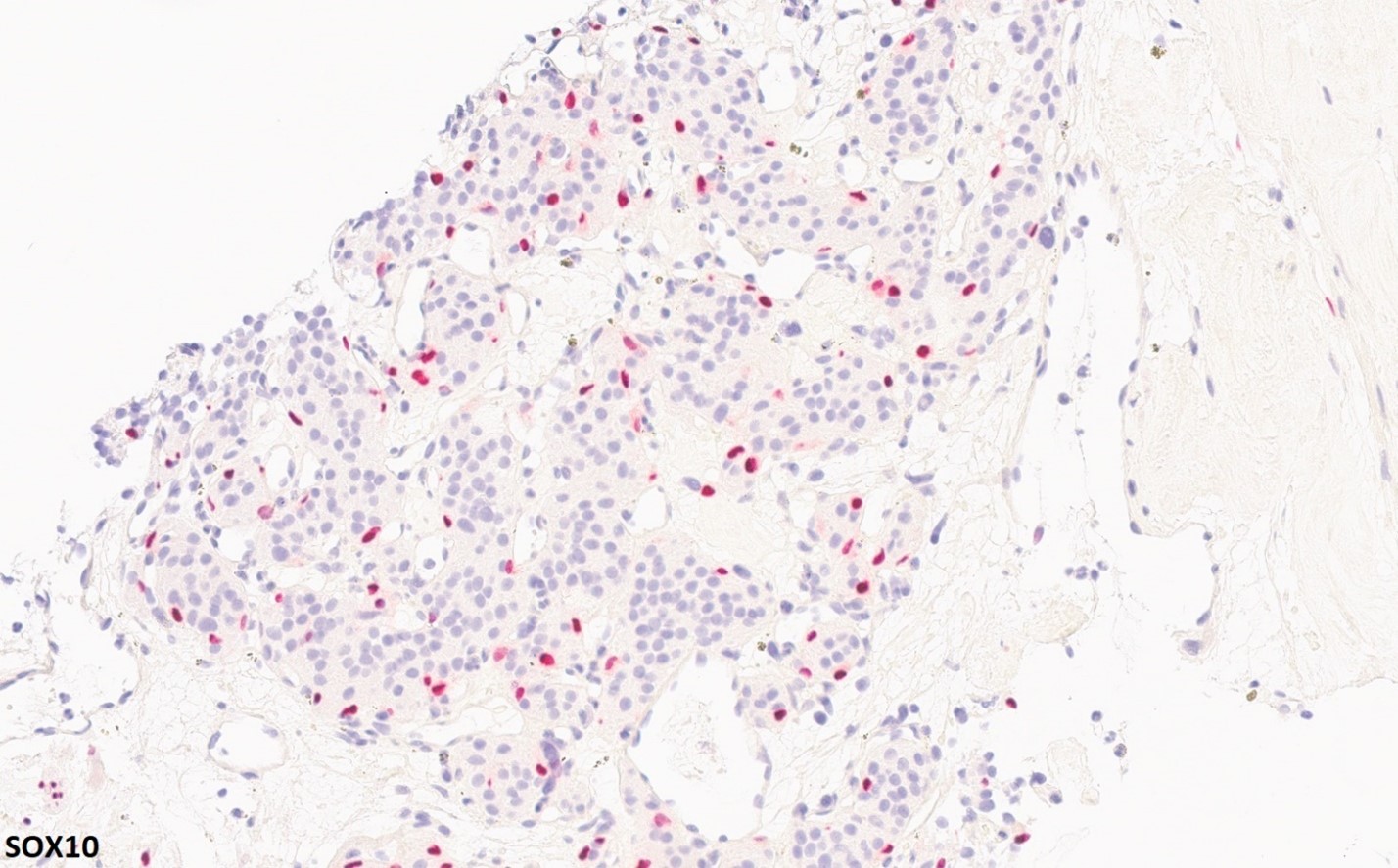

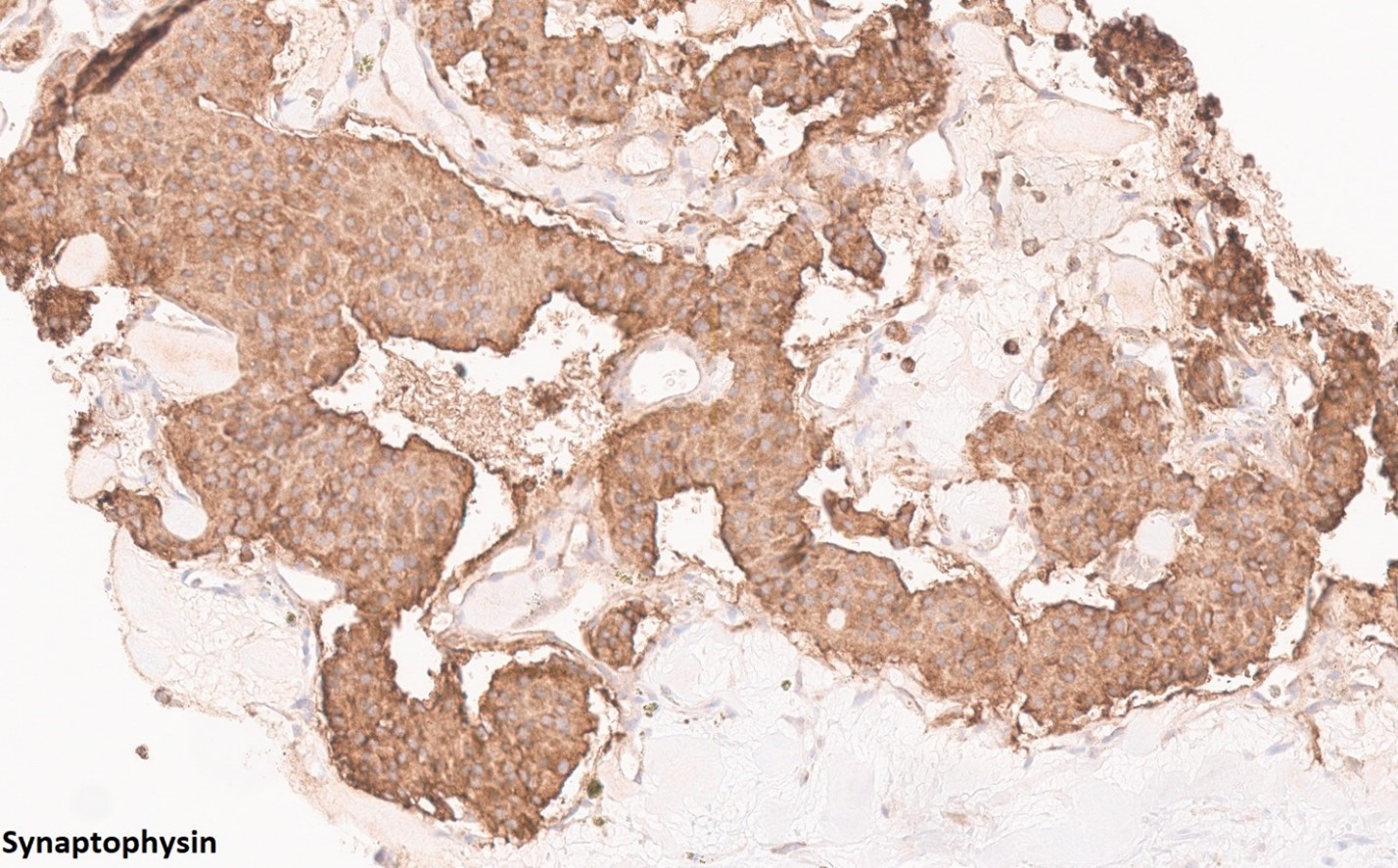

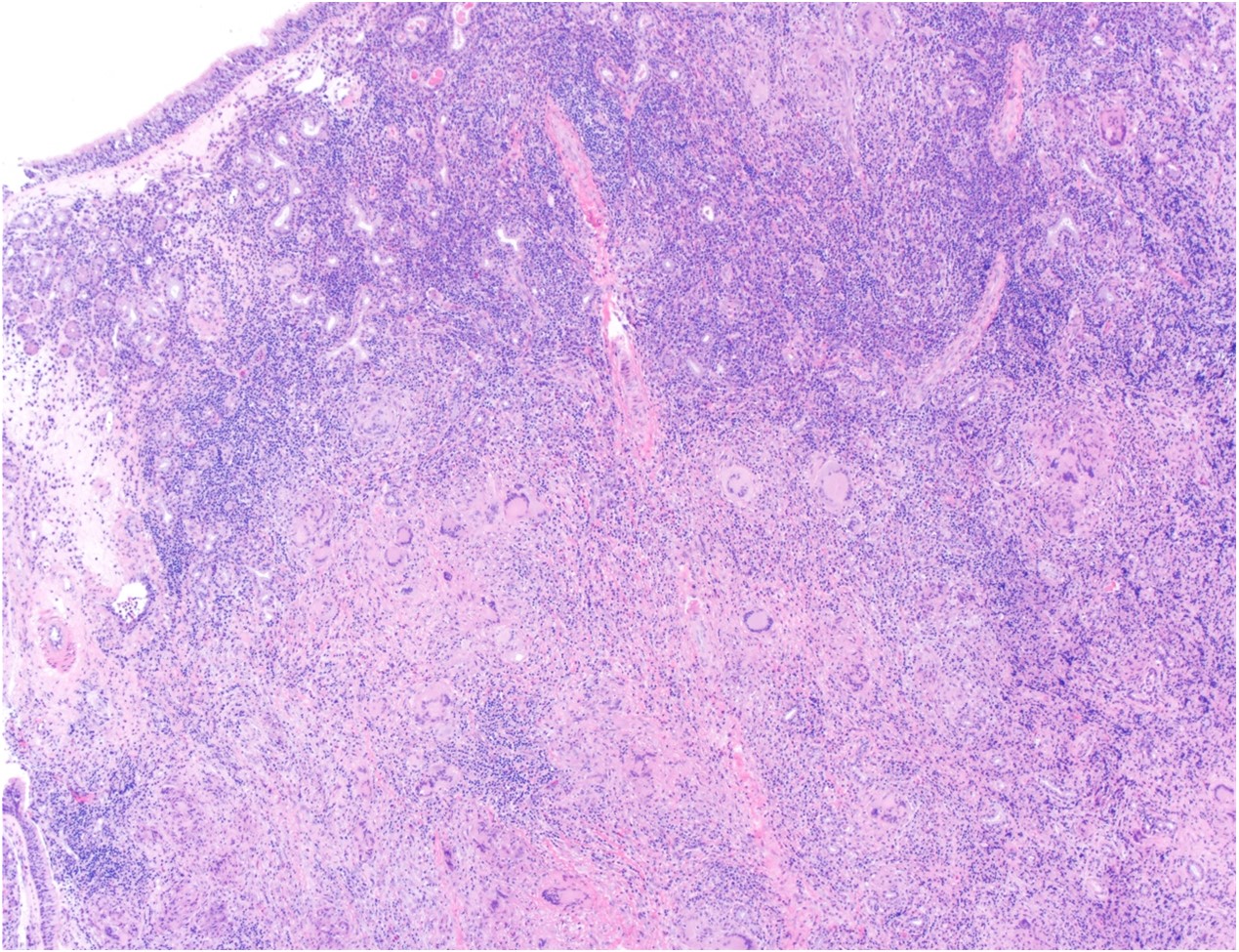

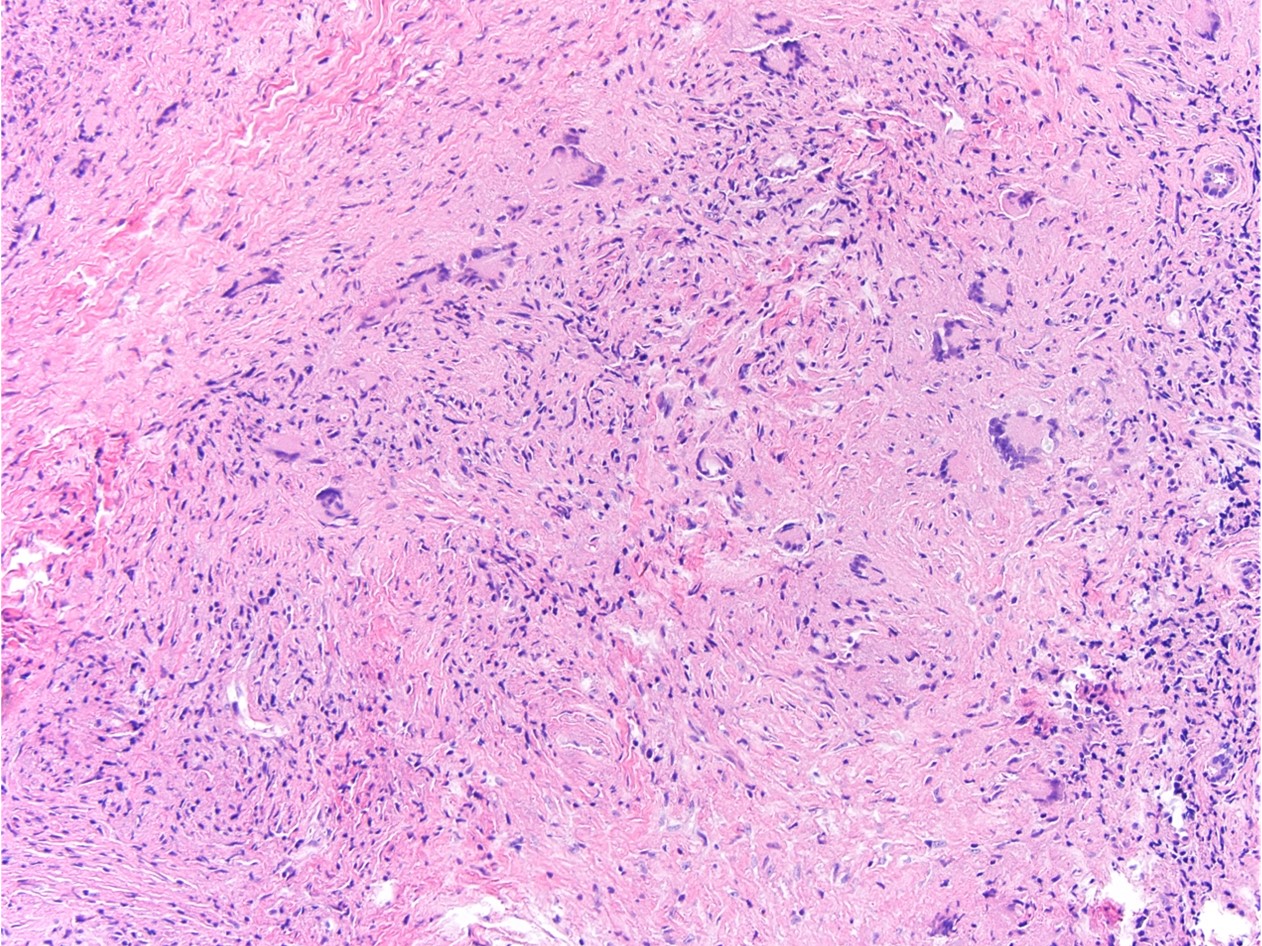

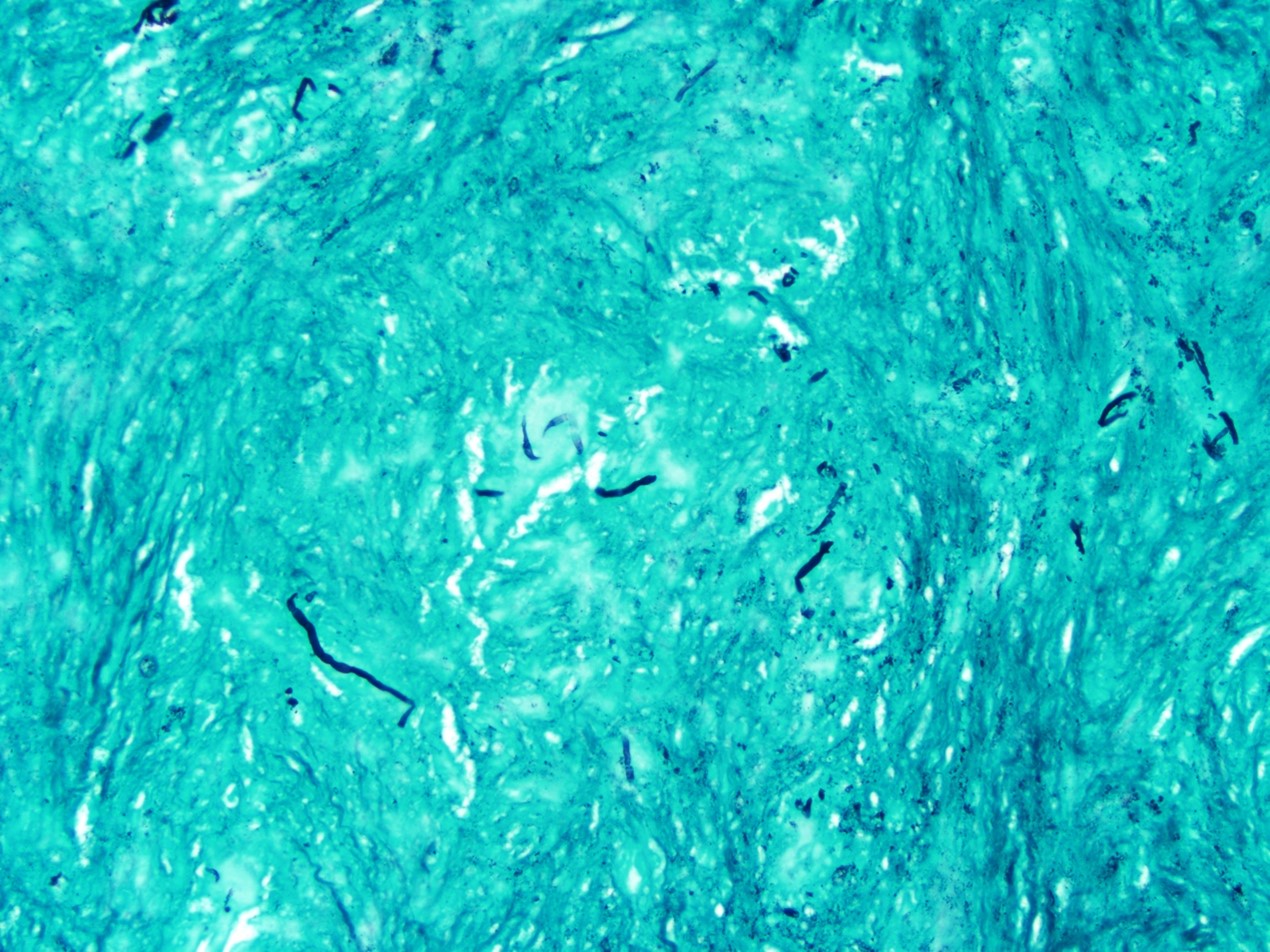

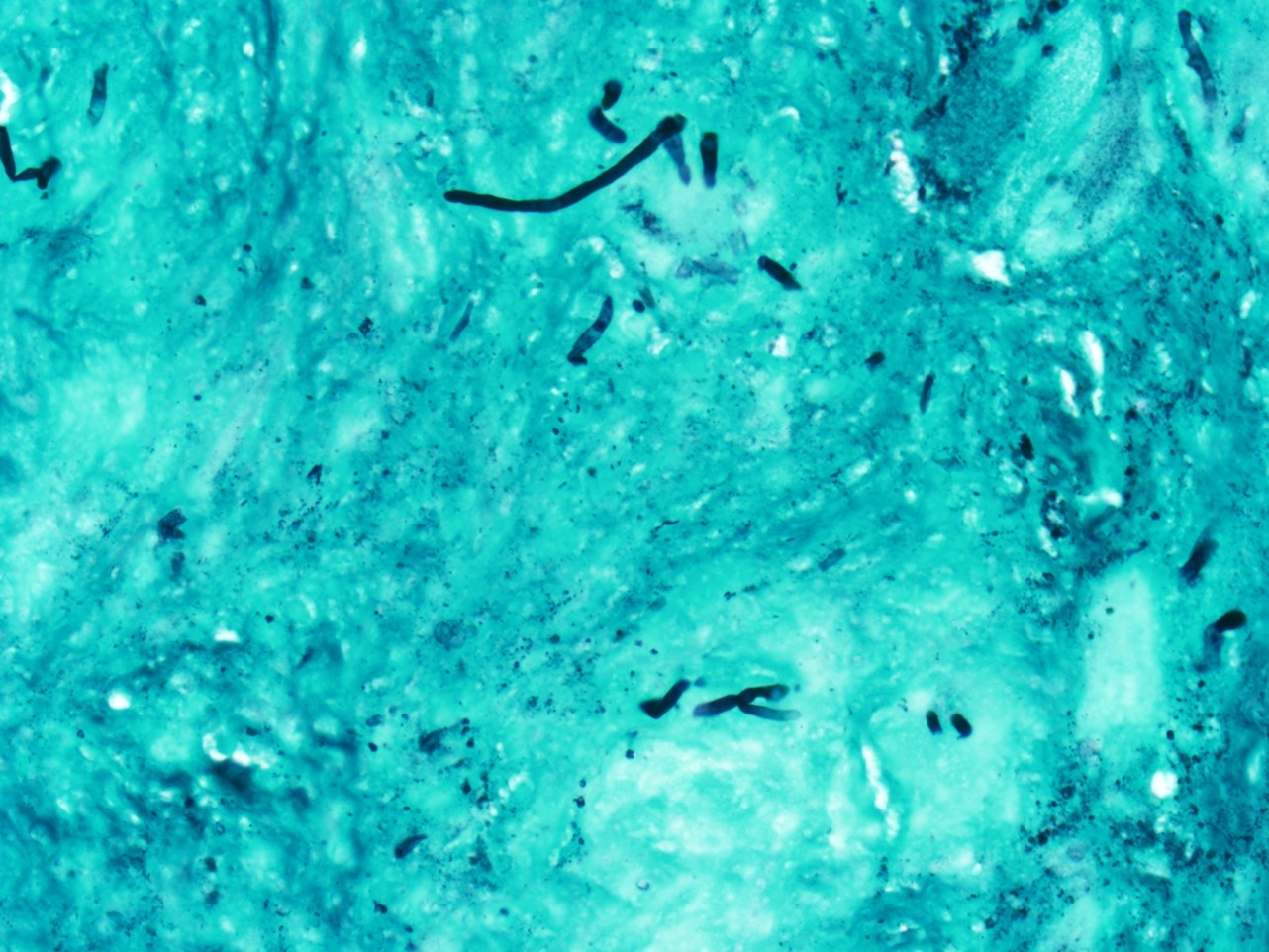

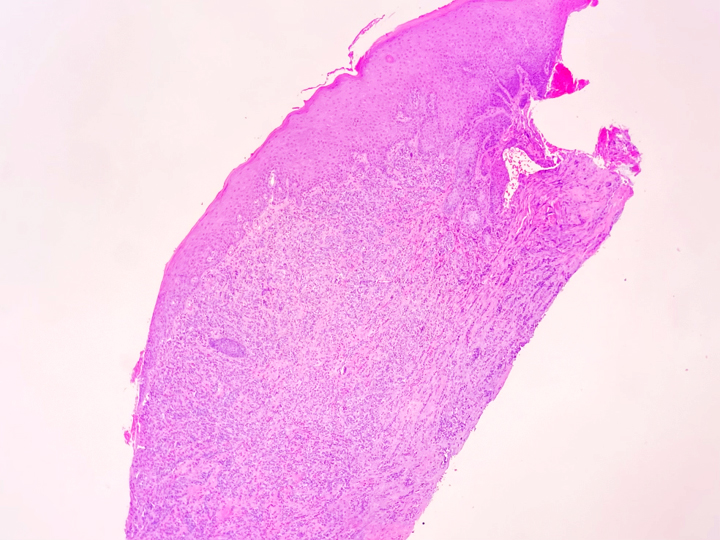

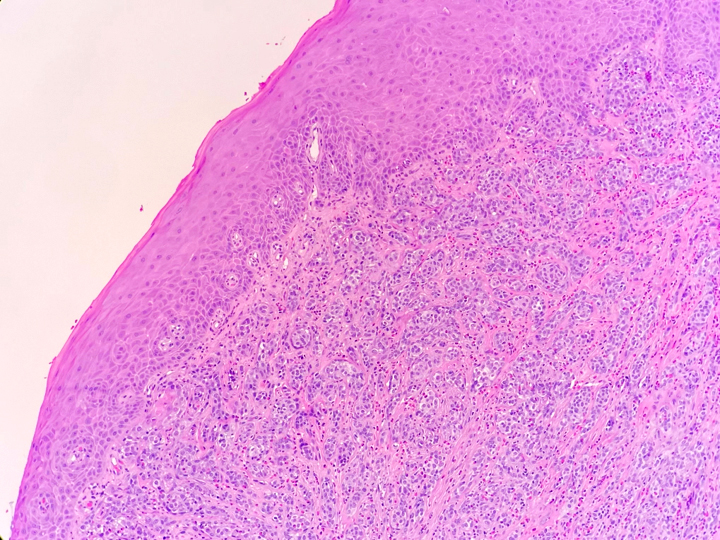

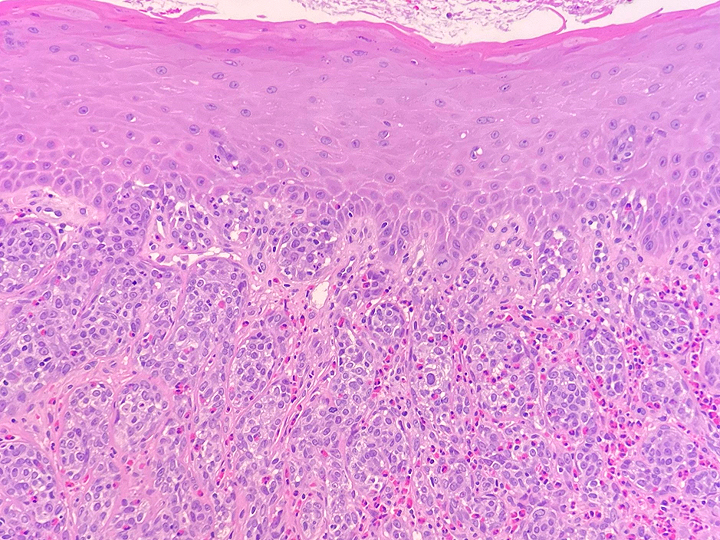

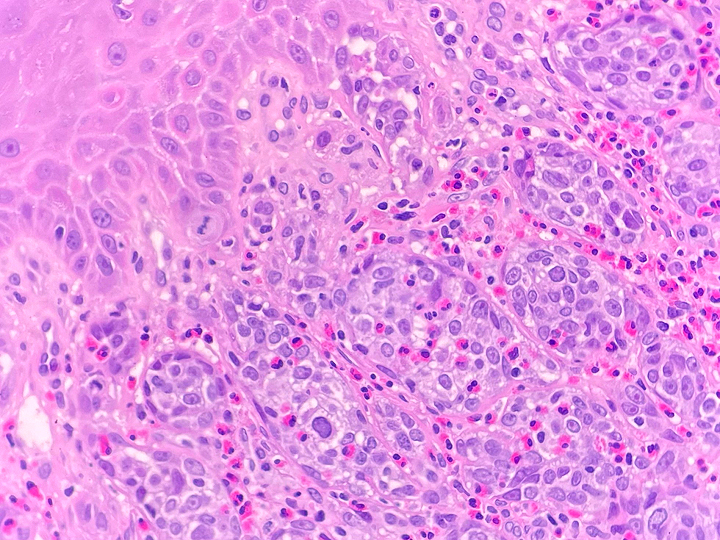

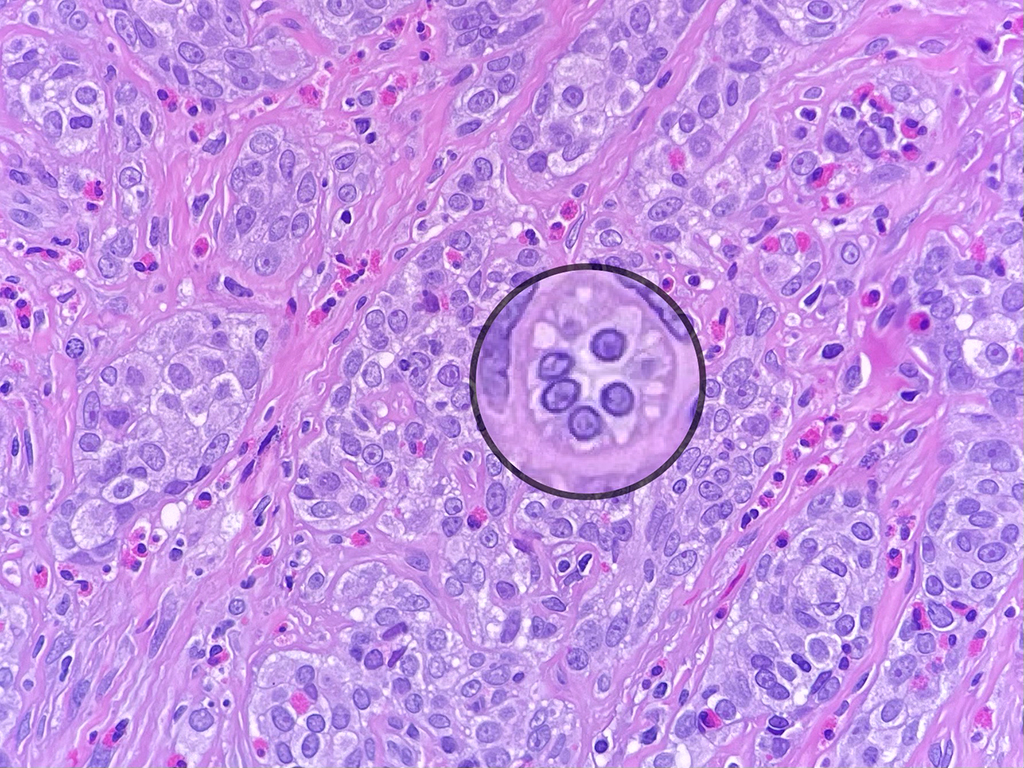

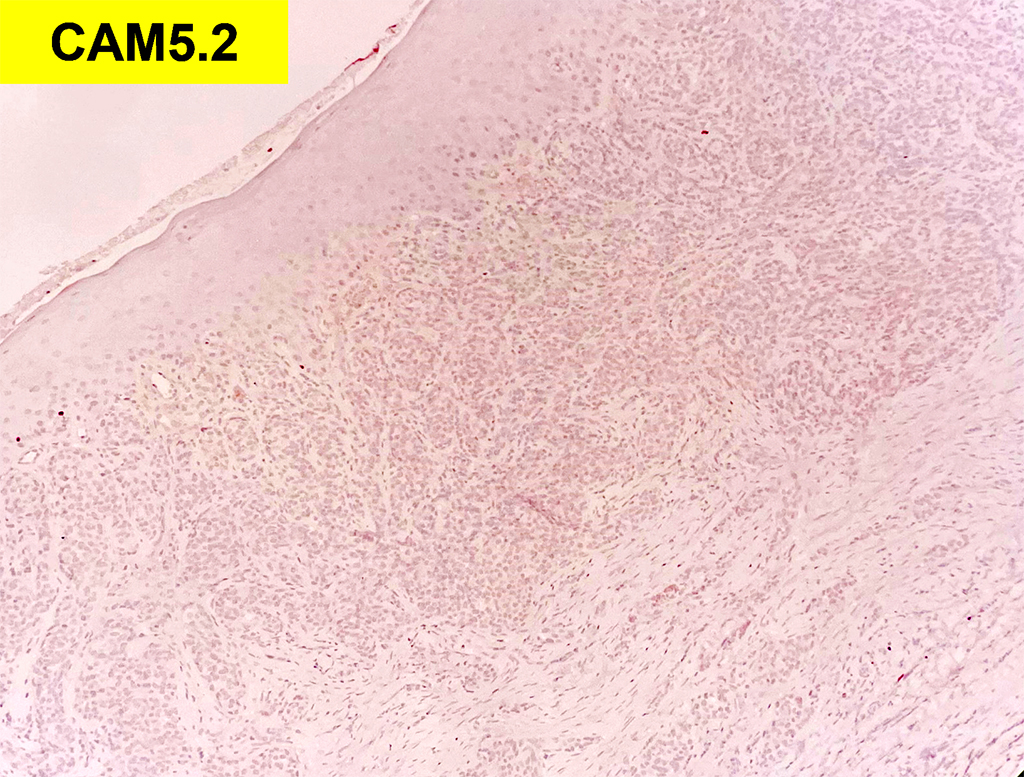

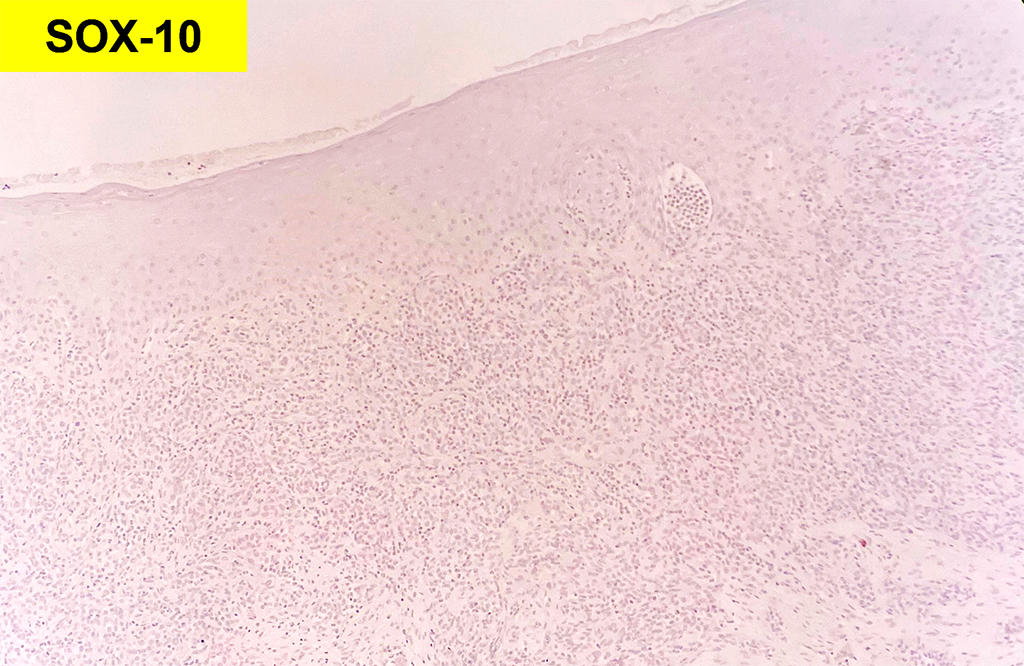

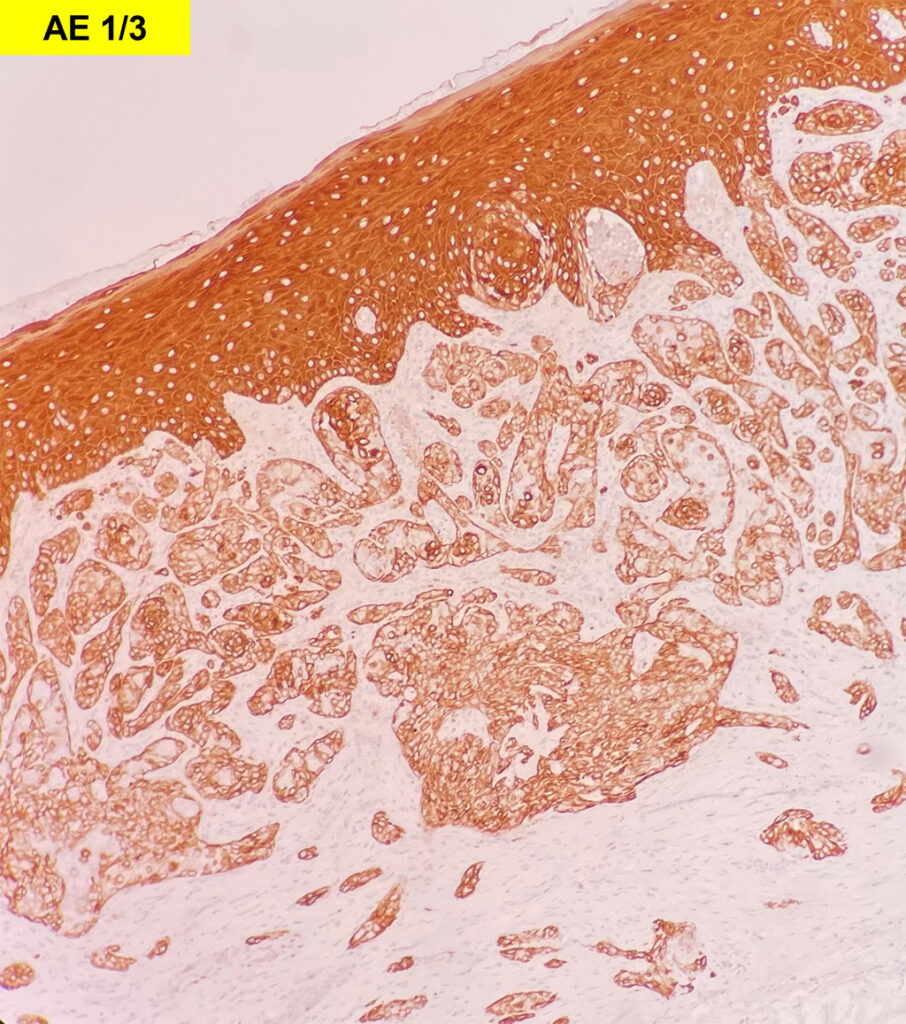

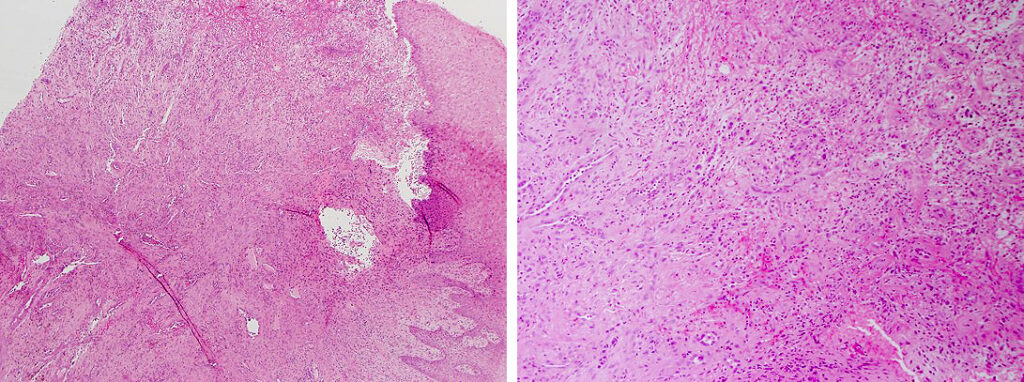

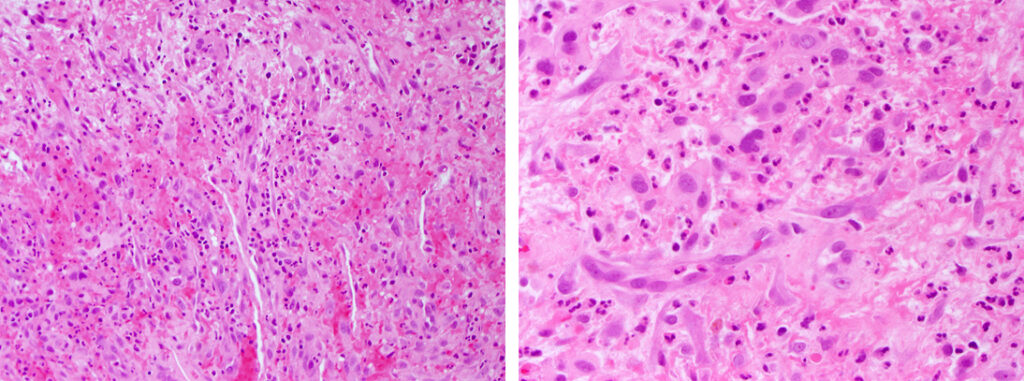

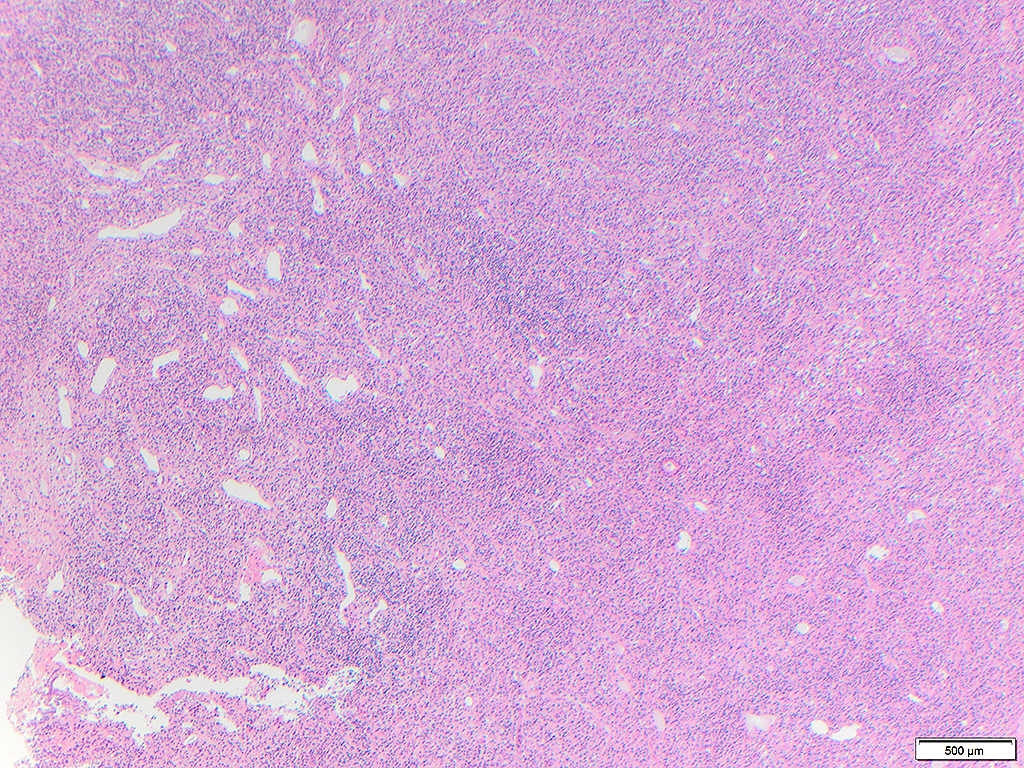

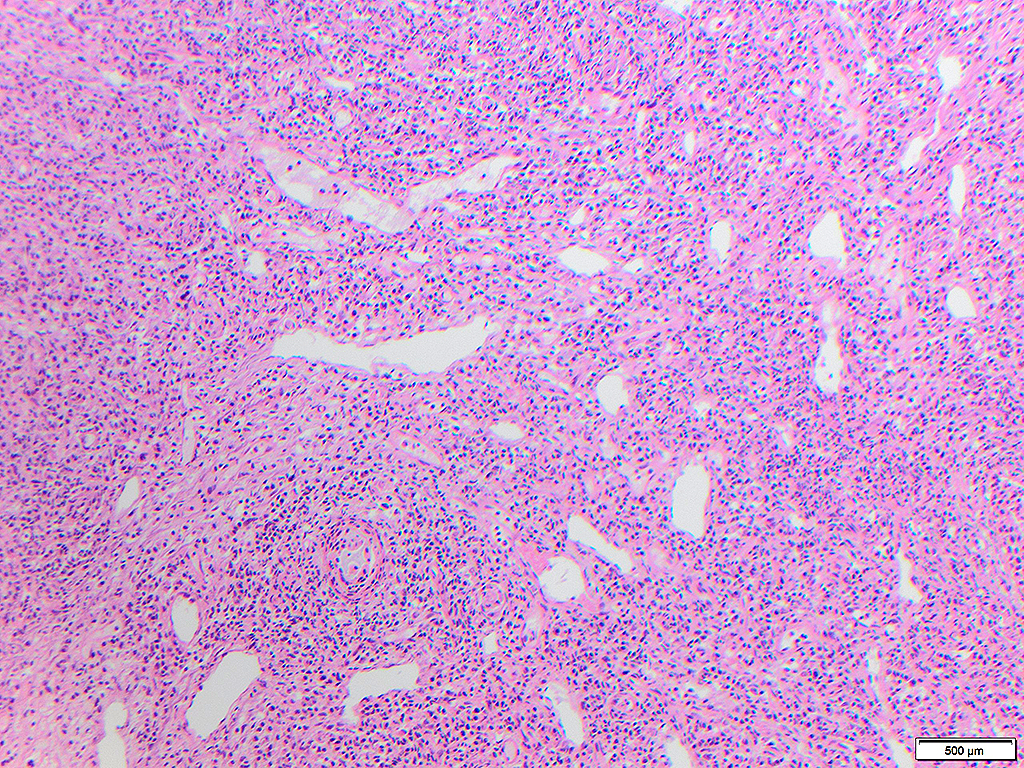

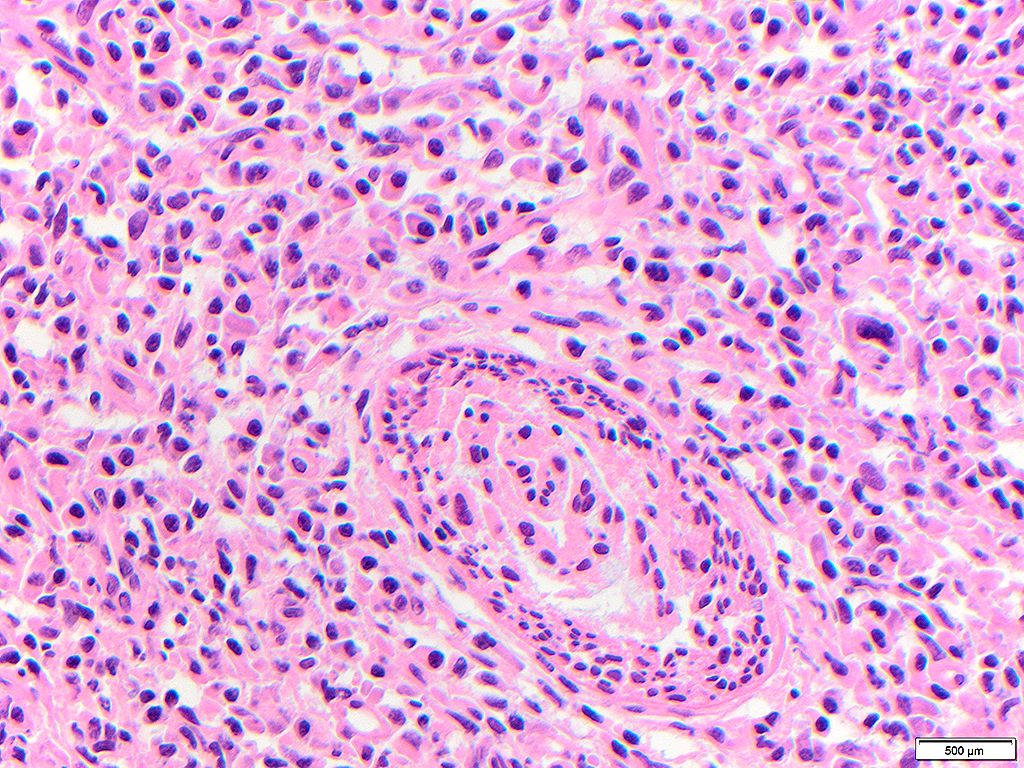

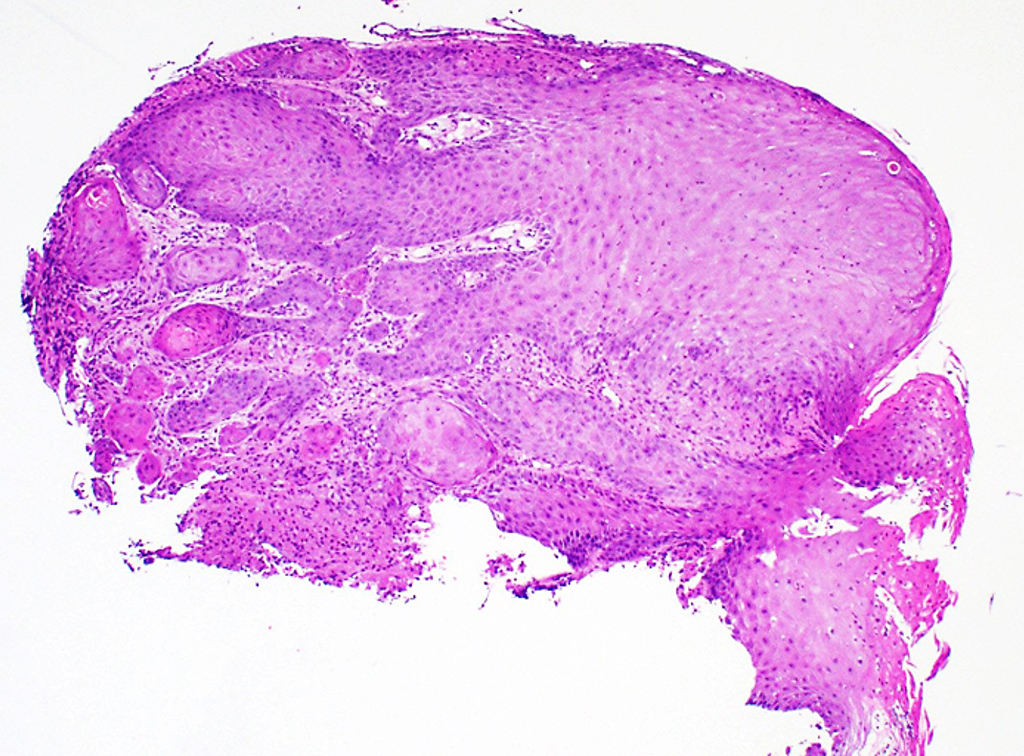

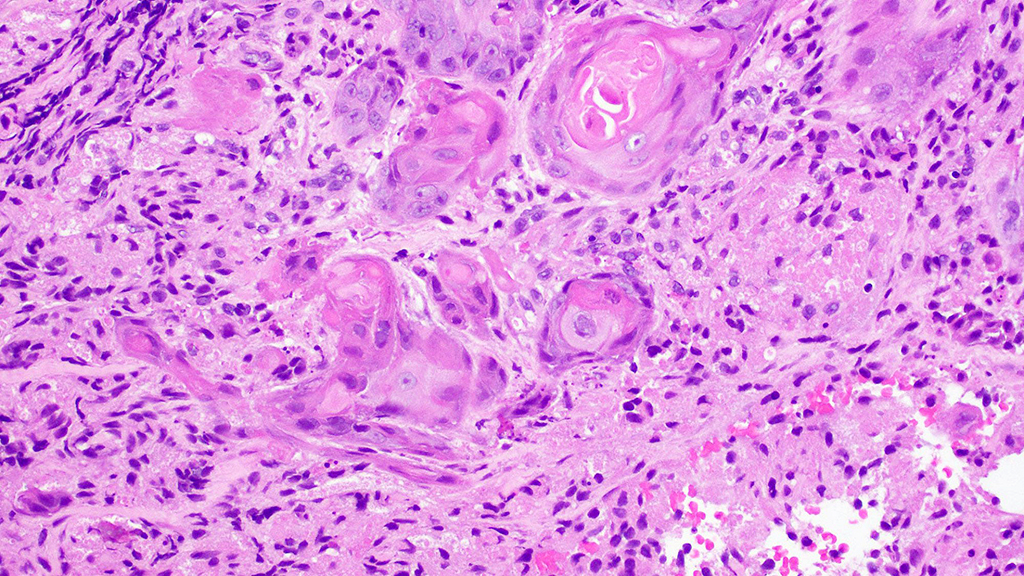

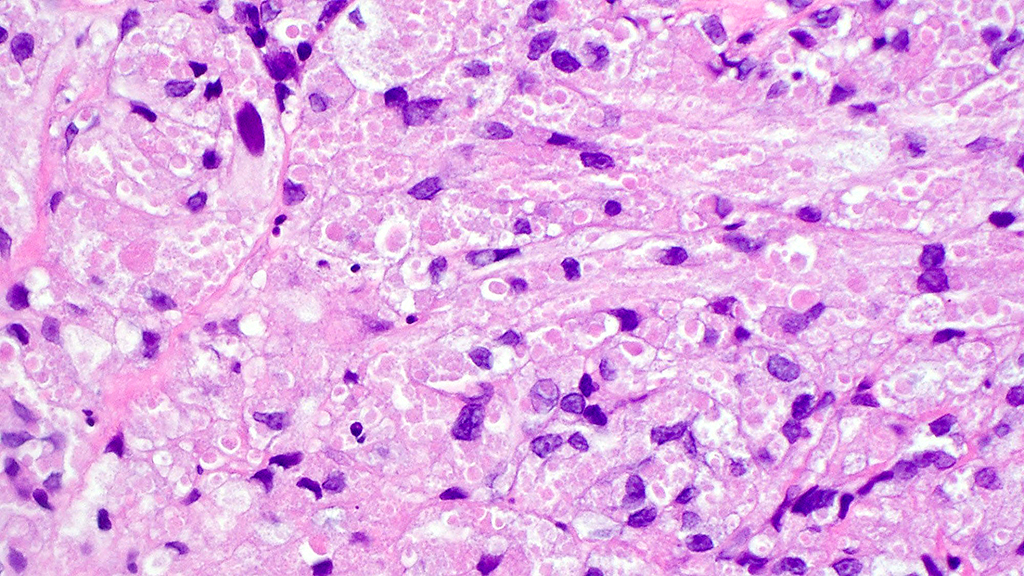

Histologically, chordomas are classified into three types; conventional chordomas, chondroid chordomas, and dedifferentiated chordomas. Conventional chordomas are generally characterized by cords and strands of intermediate to large epithelioid cells with abundant cytoplasm and large hyperchromatic nuclei. However, they can also be composed of smaller, more stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm. The identification of scattered so-called ‘physaliphorous’ cells, characterized by abundant mucin-filled vacuolated cytoplasm (giving them a “bubbly” appearance), are a useful diagnostic feature. Abundant myxoid stroma and a lobulated growth pattern separated by fibrous septae are frequently seen. Chondroid chordomas (~5% of chordomas) are characterized by areas of immature chondroid matrix while dedifferentiated chordomas (~5% of chordomas) are characterized by atypical spindle cells/high-grade sarcomatous elements. Chordomas are typically positive for pancytokeratin, EMA, S100, and brachyury (highly sensitive and specific). Additionally, mucicarmine and/or PAS can be used to highlight intracellular mucin.

The metastatic chordoma presented in this case was positive for pancytokeratin, EMA, S100, and brachyury. The tumor was composed of cords, nests, and single atypical epithelioid cells in a highly reactive background. Characteristic physaliphorous cells were not identified by either H&E or mucicarmine. Given the initial non-specific findings, the patient’s clinical history including the concerning radiologic features, was invaluable in working up this case. Review of the patient’s medical history revealed that he had a remote history of sacral chordoma with pelvic metastases approximately 20 years ago. Until his recent presentation, his disease process was notable for multiple pulmonary masses/nodules, relatively stable bony disease, and what was presumed to be a stable right maxillary sinus mucus retention cyst.

Chordomas are characterized by a high regional recurrence rate of over 50% following treatment with surgical resection ± radiotherapy. Additionally, late recurrences greater than 10 years are relatively common, necessitating long term follow-up. The rate of metastasis has been estimated at around 15-20%, with the most common sites being lung, liver, bone, skin, and lymph nodes. However, a number of rare secondary sites of metastasis have been reported in the literature; including heart, breast, tongue, mandible, genitalia, fingertips, and orbit. Without appropriate clinical history these lesions can present a diagnostic challenge.

References

Young VA, Curtis KM, Temple HT, Eismont FJ, DeLaney TF, Hornicek FJ. Characteristics and Patterns of Metastatic Disease from Chordoma. Sarcoma. 2015;2015:517657.

Rohatgi S, Ramaiya NH, Jagannathan JP, Howard SA, Shinagare AB, Krajewski KM. Metastatic Chordoma: Report of the Two Cases and Review of the Literature. Eurasian J Med. 2015;47(2):151-154.

McPherson CM, Suki D, McCutcheon IE, Gokaslan ZL, Rhines LD, Mendel E. Metastatic disease from spinal chordoma: a 10-year experience. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006 Oct;5(4):277-80.

Wasserman JK, Gravel D, Purgina B. Chordoma of the Head and Neck: A Review. Head and Neck Pathology. 2018 Jun;12(2):261-268.

Karpathiou G, Dumollard JM, Dridi M, Dal Col P, Barral FG, Boutonnat J, Peoc’h M. Chordomas: A review with emphasis on their pathophysiology, pathology, molecular biology, and genetics. Pathol Res Pract. 2020 Sep;216(9):153089. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.153089. Epub 2020 Jun 29. PMID: 32825957.

Quiz Answers

Q1 = D. A malignant process derived from embryologic remnants

Q2 = B. Brachyury