A 36-year-old man presented with left eyelid drooping for one year along with progressively worsening headaches, blurry vision and diplopia for the prior month. A CT scan of the head showed a mass in the left maxillary sinus measuring 5.5 x 4.4 x 3.3 cm with bony destruction of the maxillary sinus walls and extension into the soft tissues of the posterior left orbit. The clinical and radiographic findings were highly suspicious for malignancy. A biopsy of the mass was subsequently performed. Representative CT scan radiographic images of the mass along with images of the surgical pathology are shown below.

1. To qualify as chronic invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (CIFR), symptoms must be present for at least:

2. Which of the following histopathologic features is seen in chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (CGIFR)?

Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis

Chronic granulomatous invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (CGIFR) is an uncommon subtype of fungal rhinosinusitis (FR), which includes a wide range of pathologies from fungal infection of the paranasal sinuses. FR can first be broadly divided into either non-invasive or invasive subtypes based on the presence or absence of organism extension into the submucosa (and deeper tissues) by histopathology. Non-invasive FR includes fungus ball, saprophytic fungal infestation, and allergic FR. Invasive FR is less common than non-invasive FR and is divided into three major categories based on duration of symptoms and histopathologic features. These are 1) acute invasive FR (AIFR), 2) chronic invasive FR (CIFR), and 3) CGIFR. AIFR typically presents with a combination of congestion, rhinorrhea, headache, dizziness, fever and orbital swelling. Changes in vision and mentation, including diplopia, may also be present, as well as proptosis and tenderness to palpation of the facial sinuses. In the chronic forms of invasive FR, systemic symptoms tend to be absent, and patients typically present after an extended period of time with unilateral nasal obstruction or as a mass in the paranasal sinuses or nasal cavity. With longer delay in seeking medical care, visual and neurologic complications may develop.

AIFR consists of acute onset and aggressive progression of symptoms with a duration <30 days by definition. Symptoms are due to invasion of hyphae into the submucosal vasculature with resulting thrombosis, tissue infarction, and spread outside the sinuses into nearby bone and soft tissue. AIFR most commonly occurs in severely immunocompromised patients, in particular those with neutropenia resulting from hematologic malignancy, as well as patients with bone marrow or solid organ transplant, HIV, or those receiving systemic chemotherapy. Poorly controlled diabetes with diabetic ketoacidosis is also a well-known risk factor for AIFR. It is critical to diagnose AIFR swiftly as infection can progress rapidly, spread to the CNS and become fatal. The reported mortality rate is still approximately 50% but appears to be decreasing over time. Histopathologic findings include infarcted mucosa with minimal inflammatory reaction and vascular thrombosis with angioinvasive fungal hyphae. GMS and PAS special stains can help reveal vascular and soft-tissue invasion of fungus and better highlight the hyphal morphology. Cultures from AIFR most commonly grow Aspergillus sp. and Rhizopus sp. of the Zygomycetes order, with the former being more commonly isolated in the immunocompromised population and the latter being more commonly isolated in the diabetic population. Treatment consists of surgical debridement followed by intravenous antifungal therapy, as well as treating the individual’s underlying immunodeficiency, if possible.

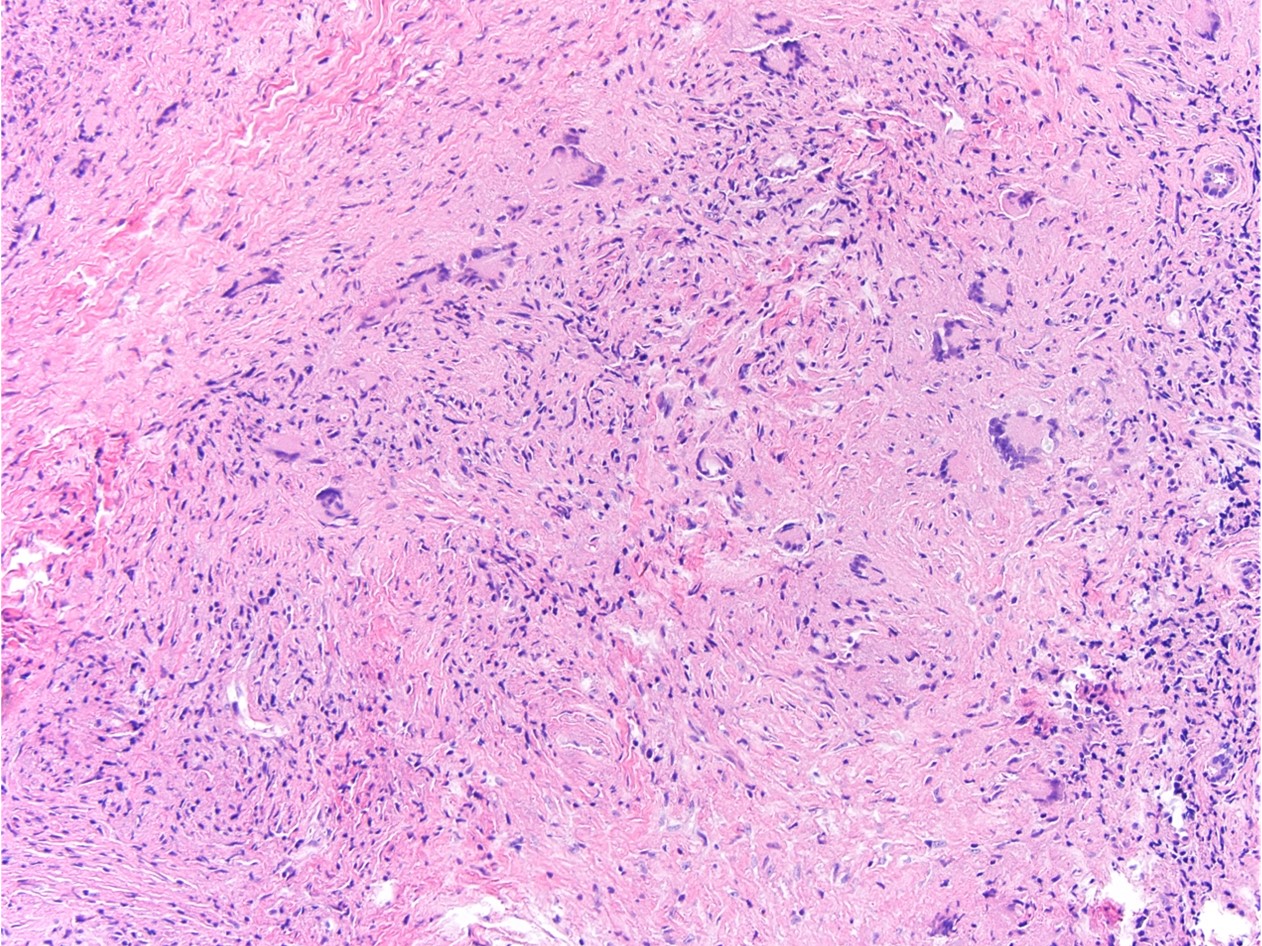

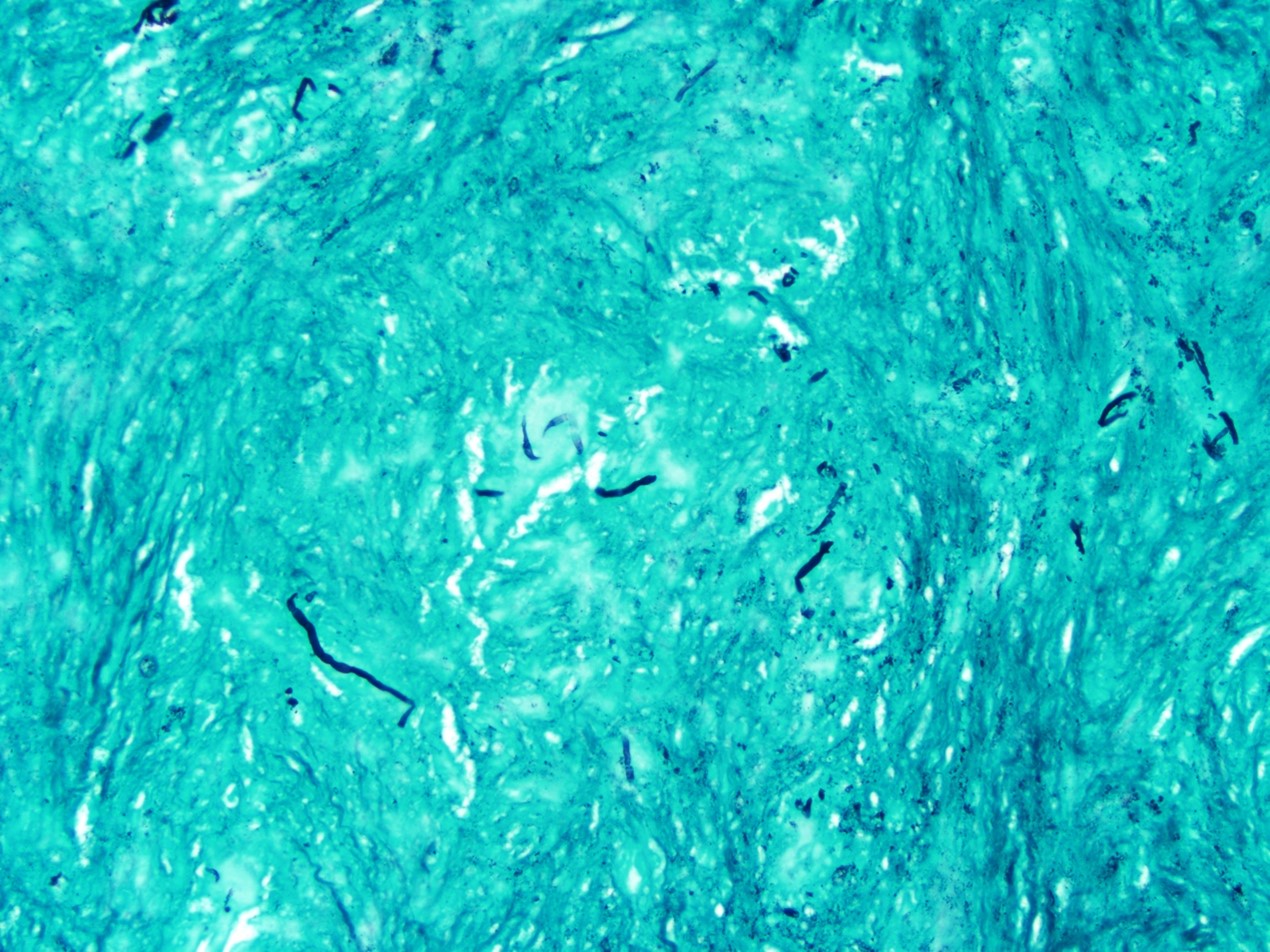

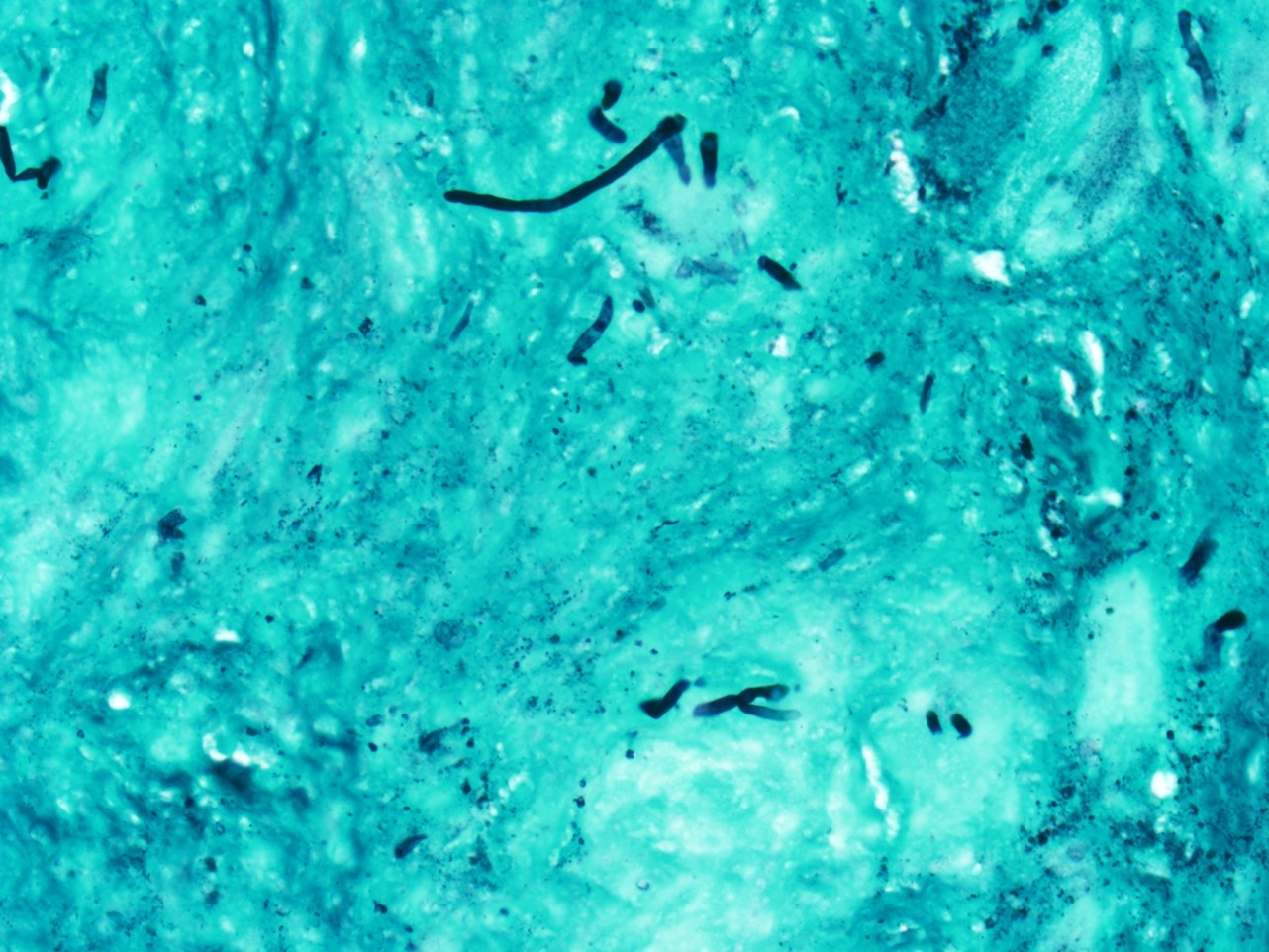

The chronic forms of invasive FR, meanwhile, occur with slower, insidious symptom onset and progression with a duration of symptoms, by definition, of >12 weeks. They are more common in arid regions including India, Sudan, the Middle East, and northern Africa, and are rarely seen in the United States. Because they can present with a mass in the paranasal sinuses, it is not uncommon for these lesions to be mistaken for cancer on imaging. CIFR and CGIFR can both present in the setting of mild immunodeficiency, such as patients with diabetes or on steroid treatment, as well as in fully immunocompetent patients. Histopathologic findings from CIFR include extensive fibrosis and chronic inflammation without granulomas. Cultures from CIFR most commonly grow Aspergillus fumigatus. Histopathologic findings in CGIFR include submucosal fibrosis and non-caseating granulomatous inflammation. Fragmented fungal hyphae can be seen in the granulomatous areas by H&E, but the organisms can be much better seen on GMS or PAS special stains. Cultures in CGIFR most commonly grow Aspergillus flavus.Despite their prolonged duration of symptoms, both CIFRS and CGIFR also require prompt recognition and treatment with surgical debridement followed by systemic antifungal therapy.

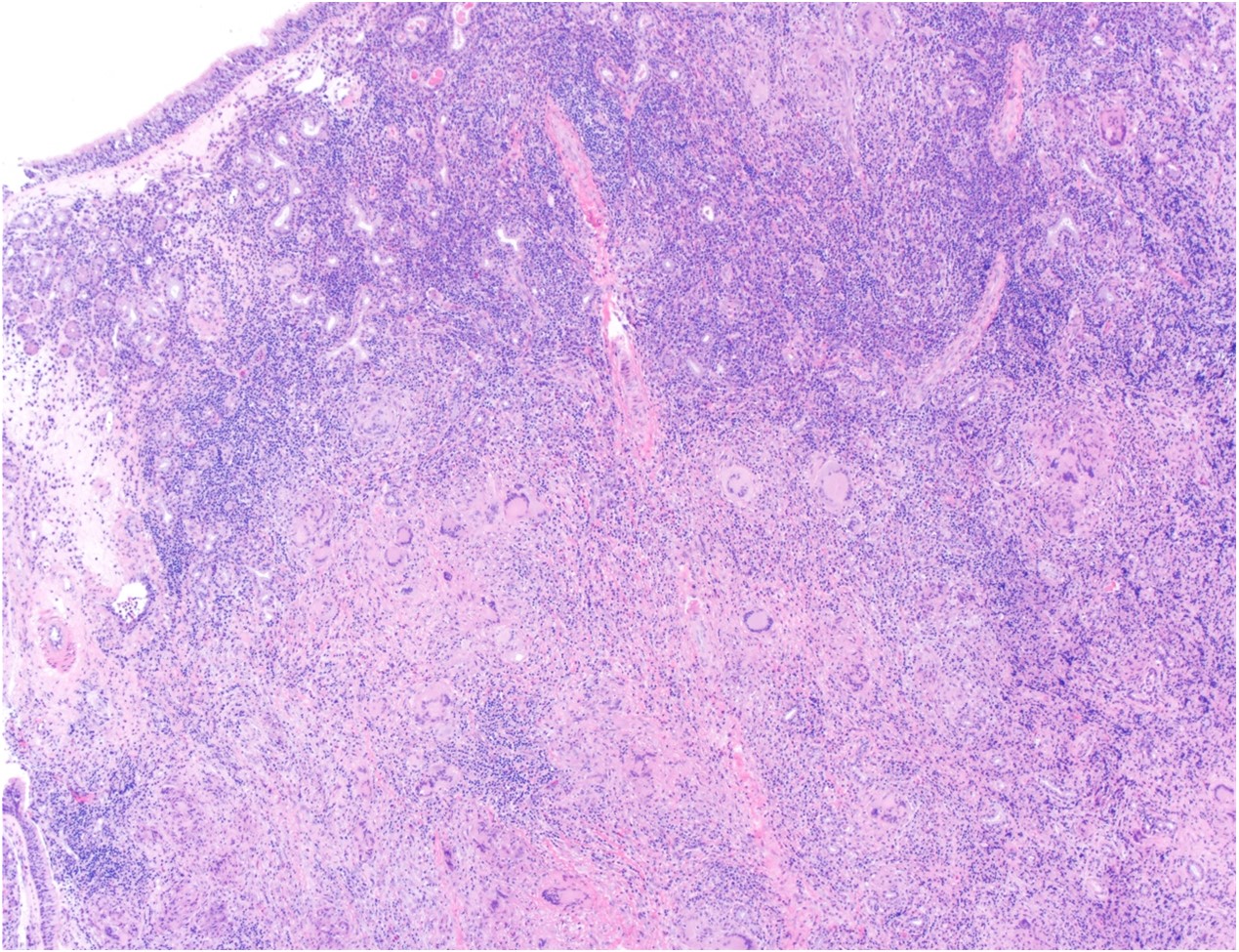

In our case, the patient did not have any known underlying immunodeficiencies nor any risk factors that would contribute to immunosuppression, and clinical suspicion was highest for malignancy. H&E stains revealed sinonasal mucosa with extensive submucosal fibrosis and associated poorly formed granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells, mild chronic inflammation, scattered eosinophils, and foci of hyaline necrosis and dystrophic calcification. A GMS stain showed numerous scattered and fragmented fungal hyphae in the fibrous tissue. The hyphae were narrow and regular with obvious septation. Subsequent fungal cultures grew non-fumigatus Aspergillus species.

References

- Akhondi, Hossein, et al. “Fungal Sinusitis.” StatPearls, 19 Jan. 2022, www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.proxy.library.vanderbilt.edu/books/NBK551496.

- Alarifi, Ibrahim, et al. “Chronic Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis: A Case Series and Literature Review.” Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, vol. 100, no. 5_suppl, 2020, pp. 720S-727S. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561320904620.

- Craig, John R. “Updates in Management of Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis.” Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head & Neck Surgery, vol. 27, no. 1, 2019, pp. 29–36. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1097/moo.0000000000000507.

- Deutsch, Peter George, et al. “Invasive and Non-Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis—A Review and Update of the Evidence.” Medicina, vol. 55, no. 7, 2019, p. 319. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55070319.

- Montone, Kathleen T., et al. “Fungal Rhinosinusitis: A Retrospective Microbiologic and Pathologic Review of 400 Patients at a Single University Medical Center.” International Journal of Otolaryngology, vol. 2012, 2012, pp. 1–9. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/684835.

- Montone, Kathleen T. “Pathology of Fungal Rhinosinusitis: A Review.” Head and Neck Pathology, vol. 10, no. 1, 2016, pp. 40–46. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-016-0690-0.

- Montone, Kathleen T., and Virginia A. LiVolsi. “Inflammatory and Infectious Lesions of the Sinonasal Tract.” Surgical Pathology Clinics, vol. 10, no. 1, 2017, pp. 125–54. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.path.2016.11.002.

- Sharif, Muhammad Shahid, et al. “Frequency of Granulomatous Invasive Fungal Sinusitis in Patients with Clinical Suspicion of Chronic Fungal Rhinosinusitis.” Cureus, 2019. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4757.

- Singh, Ajay Kumar. “Fungal Rhinosinusitis: Microbiological and Histopathological Perspective.” JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH, 2017. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2017/25842.10167.

Quiz Answers

Q1 = C. The definition of chronic in chronic invasive (including granulomatous) fungal rhinosinusitis is symptom duration of > 12 weeks.

Q2 = B. Chronic invasive granulomatous fungal rhinosinusitis (CIGFR) shows extensive tissue fibrosis.